How the IRR Can Shape Sponsor Behavior

The most common way sponsors structure their deals is by using an IRR hurdle rate that, once achieved, enables them to earn a larger share of a deal’s profits, however there are challenges with this approach, particularly when there is economic turmoil.

On the surface, a high IRR may appeal to investors. The logic behind its use is premised on the thesis that sponsors will be motivated to work harder to achieve higher returns for their investors if there are performance hurdles in place that concurrently benefit them directly.

For example, a deal might start with an 8% preferred return that becomes a 70/30% split in favor of the investors until investors receive a 15% IRR and then the profit split shifts to 50/50%. On its face, therefore, the sponsor is motivated to get investors at least a 15% IRR before getting to split profits 50/50.

This seems reasonable, but few people realize the limitations of IRR—including how easily it can be manipulated and how it can motivate an owner to sell leaving money on the table.

In this article, we examine why IRR is a flawed hurdle rate, particularly if you believe a recession is on the horizon. As you will see, in a recessionary environment where interest rates and cap rates are rising, achieving sky-high IRRs becomes more difficult. Therefore, sponsors who use IRR as the hurdle rate may inadvertently take on risks or make decisions that are not necessarily aligned with either theirs or their investors’ better interests.

Instead of IRR, we will show you why using the equity multiple as the hurdle helps to ensure all parties’ interests remain aligned and that returns to everyone can be maximized.

Learn more about our investment strategy and join the waitlist for our next opportunity.

What is the IRR?

The IRR, or the internal rate of return, measures the total annualized return on an investment. It is the percentage rate earned on each dollar invested during the investment’s entire hold period.

IRR places significant emphasis on the time value of money, e.g. when money is returned to investors relative to when the original investment(s) was made.

For example, let’s say two deals eventually return the same amount of money. IRR assumes that the investor who earns that money sooner is better off than someone who doesn’t see that money until later. This concept assumes that money earned sooner is more valuable than the same amount of money earned later for two reasons: first, money earned now can be reinvested sooner (subject to capital gains or other taxes), thereby earning even more money for an investor. Second, the simple nature of inflation can eat away at overall profits if that money is not returned to investors until a later date.

Here is a simple example.

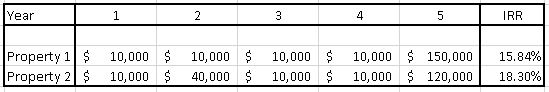

Let’s say someone invests $100,000 each into two separate deals. The returns for each property are distributed as follows:

As you can see, each property generates $190k after the end of five years. The big difference is that Property 2 generates an oversized return in Year 2, which results in a lower payout at the end of Year 5. The distribution of profits in this manner results in a higher IRR, although total profits are the same.

In this example, the IRR for Property 1 is 15.84% whereas the IRR for Property 2 is 18.3%. This is because IRR heavily weights when someone earns their return, not just the total returns. The dollars returned in Year 2 are considered more valuable than those earned in Year 5.

How is IRR Measured?

IRR is calculated by taking the yearly cash flows from an investment property (real and projected) and then applying a discount rate to cash flows as they are earned further into the future. This includes the cash flow from monthly and/or annual rent payments as well as the proceeds from the eventual sale or refinance. The IRR assumes that the sponsor can make thoughtful and relatively accurate projections about the amount of cash flow a deal will generate, sometimes well into the future.

This use of the IRR is a way for professional real estate investors to determine the value of an asset that they may wish to acquire. They will look at the projected cash flow for the entire lifecycle of a deal, project the ultimate sales price, apply a discount rate (the IRR) to those numbers, and end up with a price that they are willing to pay for the asset that will yield the desired returns when the asset is sold.

Passive investors are apt to use the IRR to compare real estate investment opportunities against each other but herein lies the hazard as we will discuss.

Why Sponsors Use IRR as a Hurdle

IRR is often used as a “hurdle rate” in private equity real estate investing. To understand how this works, someone must first understand the basics of a real estate waterfall.

In short, a real estate waterfall describes how profits will be split, to whom, and when. It can be thought of as a series of pools that fill up with cash. Once a pool is full, the excess cash spills over into the pools below.

Many waterfalls are structured using what is known as a “promote”. The promote is when a sponsor becomes eligible to receive a disproportionate share of the profits. The promote is usually based on a pre-defined “hurdle” rate. In many cases, IRR is used as the hurdle rate. For example, the profits may be distributed 70/30 between investors (70%) and the sponsor (30%) until investors reach a certain internal rate of return. Once meeting that “hurdle,” the split might shift to 60/40 or even 50/50 as time goes on.

To be able to use the IRR as a hurdle, however, a sale of the asset must be assumed because that is typically where all the investors’ capital is returned and promote splits are calculated and distributed. Without a sale, it will likely be impossible for a sponsor to ever hit an IRR hurdle.

Take, for example, a deal where there is an 8% preferred return that, once hit, converts to a 70/30% split of profits to the investors and sponsor respectively until investors receive a 15% IRR and then splits move to 50/50%. It would be extremely rare to find a real estate deal that yields compounded cash returns of 15% annually so for the sponsor to hit the highly motivating 50% share of profits, the only option they are going to have is to sell the asset.

And the big problem is that the sooner they sell, as illustrated in the first example above, the higher the IRR and so the faster they reach the higher splits for themselves. This can create a misalignment of interest, especially when prices are turning downward during a recession, if a sponsor’s only hope of earning the most favorable splits in a deal is to sell the project as quickly as possible.

IRR is one of several “hurdle” rates that sponsors can use with their promote structure. The equity multiple is another hurdle that can be used and that creates a more equitable split of profits without subjecting the sponsor to undue pressure to exit a deal more quickly than they would like. However, IRR tends to be favored among sponsors because it is a simple number to read, (though not so easy to understand) and there are many ways they can manipulate IRR to make it look higher – for example by accelerating the projected exit year in a proforma or actually selling early to ensure that they meet that “hurdle” rate sooner than if they were using another measure of return.

The Downsides of Using IRR as the Hurdle Rate

As discussed, when investors use IRR as the hurdle rate for promotes, it can create undue pressure on the sponsor to achieve that hurdle rate—and sooner rather than later. This results in sponsors manipulating their underwriting assumptions, intentionally or unintentionally, to inflate IRR as a means of attracting more investors to the deal. Today, investors expect deals to achieve 15-20% IRR without understanding what’s driving that calculation. It is a vicious cycle that, upon further investigation, is risky for all parties involved.

IRR is Easily Manipulated

There are many ways that IRR can be manipulated by sponsors looking to hit a hurdle rate sooner rather than later. For example, a sponsor can take on additional debt to boost IRR by reducing the amount of equity required. If the loan to value is higher than, say, 75%, this leaves little room for underperformance and increases the risk that a sponsor could lose his project to the bank. This is a particularly risky situation, particularly in a recessionary environment. (Note: At Bravante Farm Capital, we do not take on more than 50% debt).

Another well-documented way that sponsors can artificially boost IRR is by taking out what is known as a “subscription line of credit.” SLOCs and other short-term credit facilities allow sponsors to delay making a capital call. By delaying when “committed” capital is actually invested, it shortens the length of time that money is invested. And shorter investment time horizons translate into higher IRRs.

IRR Does Not Distinguish Between Cash Flow Over the Life of an Investment and Profits from Sale

Using the example above, most people would assume that Property 2 is a better investment than Property 1, at least on the basis of IRR alone. And this may be true, but there is always more to the story than that.

One of the downsides to using IRR is that it does recognize the cash flow investors receive over the life of an investment versus the profits they yield upon a sale. Instead, it aggregates the total weight of the return based on when investors get capital back, when they get cash flow during the life of a deal, and how much they get when the project is sold.

It does not provide much insight as to the details of those returns. For instance, a property might have a high IRR but may not generate any ongoing cash flow to be returned to investors. Profits may not be realized until a sale or refinance at the end of a hold period. Those returns may be oversized, therefore resulting in a high IRR, but investors may see no cash flow in the interim. For some investors, that may be fine. For others, they may prefer to earn some income in the meantime. This is why investors need to dig deeper, beyond the stated IRR, to understand a deal’s entire return profile.

IRR Can Motivate Sponsors to Sell Too Early

Many of those who work in private equity are heavily incentivized by achieving (or exceeding) aggressive IRR targets. For example, if the goal is to sell a deal in five years, the sponsor may look to sell the deal in two or three deals, which causes the IRR to skyrocket. Because it skyrockets, the individuals working on that deal make large bonuses.

On the surface, it might seem like selling a deal sooner rather than later is better for investors. They get their money out of the deal, plus their return, and can then reinvest however they so choose. The problem, however, is that this causes some people to sell before the full asset’s full potential could be realized.

This is especially problematic if you believe a recession is on the horizon.

For example, a sponsor may suggest that they can get a 19% IRR over a three-year hold period. If pricing falls and cap rates rise, that sponsor may not be able to sell for another year or longer. Increasing the hold period by just one year can slash the IRR by more than twenty percent. The longer it takes the sponsor to sell an asset, the more challenging it becomes to meet a target IRR hurdle – perhaps even to make it virtually impossible to reach.

The most successful real estate investors (Warren Buffet and others) will tell you that the best strategy is to buy and hold real estate forever. Those who adopt this mindset simply cannot think in terms of IRR because they will never hit the IRR targets, even if the income targets outperform expectations.

IRR Hinders Long-Term Wealth Creation

As noted above, IRR motivates sponsors to sell sooner than they might otherwise. This becomes problematic for those looking to generate long-term wealth. Real wealth is created through the compounding of money over time, which is measured by annualized returns. For example, a $1 million investment that earns an 8% annual return will be worth more than $10 million after 30 years due to compounding.

IRR tries to express the equivalent of an annual return, factoring in the timing of those cash flows, but in many cases, it may be that the person earning a lower annualized return is actually earning more money than the person invested in a deal with a higher IRR. For example, it may take five years for a value-add investment to be fully stabilized, at which point the NOI might double. Sponsors who sell ahead of that 5-year mark may achieve a higher IRR, but investors will be forfeiting significant, highly valuable cash flow in exchange.

Tax considerations are also a factor. One of the biggest complaints real estate syndication investors have since it became permitted in 2012, is that each time the projects they invested in are sold, they face a hefty capital gains tax bill. Obviously this is a good problem to have and one that can be ameliorated through careful tax planning, but it is an inefficient means of building long term wealth especially as investors also have to decide what to invest on next, with their after-tax gains.

The Crowdfunding Paradox

Another downside of the overuse of the IRR as a hurdle is the extent that it has become a misleading guide to investors new to private equity real estate and, consequently, a hazardous tool for sponsors to use – especially when heading into a downturn. Here’s why.

As a real estate bull market continues to lengthen after a downturn, returns to investors go down as prices go up. The more bullish a market is and becomes as the painful memories of prior crashes fade into distant memory, the investors become increasingly willing to pay higher prices for real estate which, in turn, lowers investor returns.

The problem with the way real estate syndication has become so transparent online is that instead of returns going down as the bull market lengthens, they either remain the same or continue to climb. This happens because investors unwittingly gravitate to the deals with the highest IRRs because of the erroneous belief that if a sponsor is shooting for a high IRR but miss, presumably even if they fall short, they will hit some measure of decent returns for investors.

The fallacy with this assumption is that sponsors stretching assumptions to create headline IRRs to attract investors is more likely to fail and lose all investor money. A sponsor who is more prudent with his assumptions and so ends up with lower projected IRRs than his competitors, may not raise as much money but is far more likely to survive a downturn and protect investor capital from complete loss.

Equity Multiple: A Better Alternative to IRR

A more thoughtful way to measure a deal’s profitability is to use the equity multiple. The equity multiple measures the total amount someone will earn, in real dollars, over the lifetime of an investment.

The equity multiple is calculated as follows:

Equity Multiple = Total Cash Distributed / Total Cash Invested

Total cash distributed includes cash flow distributions, periodic capital events (e.g., a cash-out refinance or recapitalization), the return of original equity invested in the deal, and property sale. The total cash invested is net of any debt used to finance the deal and does not include any earnings that are reinvested into the property.

The higher the equity multiple, the more profitable a deal is said to be.

For example, if someone invests $100,000 into a deal that earns them $250,000, it is said to have a 2.5x equity multiple. As you can see, equity multiple measures absolute returns.

The benefit of using equity multiple as the hurdle rate is that it motivates the sponsor to stay in deals longer, and while in those deals, to generate as much profit as possible. When equity multiple is used as the hurdle rate, everyone wins: if the sponsor hits that rate sooner than anticipated, it simply means there is more money to be distributed to everyone.

It is not a number that can be manipulated to artificially inflate returns as is the case with IRR. For instance, if someone approaches the sponsor to sell for a price well above what the sponsor had anticipated, they can still do so. Everyone wins in that situation. Equity multiple just ensures that the sponsor is not motivated to sell as a means of hitting an arbitrary target that jeopardizes the full value of the investment.

Related: The Investor Friendly Bravante Farm Capital Deal Structure

Conclusion

IRR is a metric that is often misunderstood and confused by investors. Those who are evaluating specific deals will want to look at both IRR and equity multiple, as these are complementary metrics. IRR accounts for the time it takes to earn a return, whereas equity multiple indicates how much an investment will return on an absolute basis.

The real issue lies not in how we analyze deals up-front, but rather, what sponsors ultimately decide to use as the hurdle rate for promotes. Those who use IRR may end up manipulating numbers or being forced to sell an asset too soon to achieve their hurdle rate. Those who use equity multiple face less pressure to exit a deal too early and can make informed decisions that will increase the value and profitability of an asset over the long term to the benefit of everyone – a true alignment of interests.

Those with a long-term investment mindset—i.e., those who value commercial real estate as a means of generating long-term, multi-generational sustained wealth—will want to invest alongside patient sponsors like we here at Bravante Farm Capital who are willing to put in the time and work needed to maximize absolute returns on behalf of their investors.

Posted By

Adam Gower Ph.D.

Bravante Farm Capital

Executive Advisor

Adam is the country's foremost expert on real estate syndication and crowdfunding and is employed by Bravante Farm Capital to work in strategic, capital formation, and investor relations roles. He is a 35+ year commercial real estate veteran with extensive knowledge of (just about) all real estate asset classes.