Farmland: More than just an inflation hedge

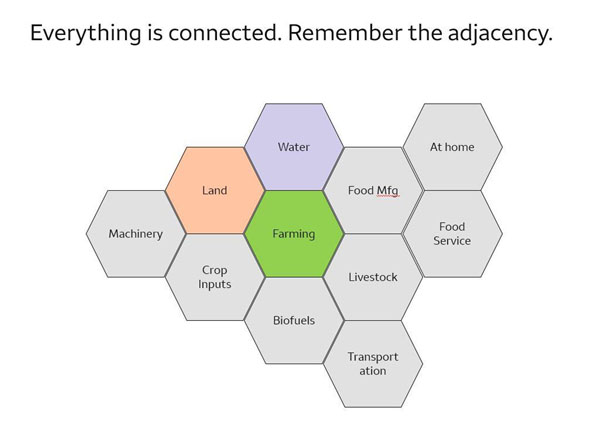

Agriculture is the world’s oldest industry, and a sleeping giant in terms of revenues – but that doesn’t mean it’s a sector that lets investors reap easy profits. In fact, agriculture is a complex system that relies on a variety of inputs and outputs.

The interconnected mosaic of farming includes not just the crops in the ground and the animals living in the pasture but also manufacturers, retailers and consumers.

The industry’s fortunes hinge on everything from this year’s precipitation to oil prices to long-term climate trends. (The adjacency concept illustrated below suggests investors looking to expand move no more than one step away from what they're currently doing.)

Source: Wells Fargo Bank

Learn more about our investment strategy and join the waitlist for our next opportunity.

The value of any given piece of farmland is affected by such outside forces as the availability of water and farmworkers. Consider the case of California, the nation’s No. 1 agriculture state, with an annual yield of $40 billion. (Iowa, a producer of corn and soybeans that’s perhaps more widely associated with agriculture, is No. 2, followed by Texas, a huge state with cattle ranches, cotton farms, dairy farms, corn and other crops.)

There’s a lot of land in California, but land without water and land without a supply of available labor is not going to be productive. And productive ground is not worth farming. So investing in California farmland requires being intensely aware of these two primary inputs of water availability and labor.

Everything revolves around water in particular. Millions of acres in California could be farmed if water were plentiful, but water is in short supply. And so those millions of acres can't be farmed. This isn’t an issue only in California. The Upper Midwest, the Plains, Montana and Wyoming endured a severe drought last year, so the weather affects every geographic area.

Being aware of the weather is a key component in understanding valuation patterns in agricultural real estate. In other words, simply owning land in California is not the path to strong returns. Even with its water constraints, California has experienced incredible productivity.

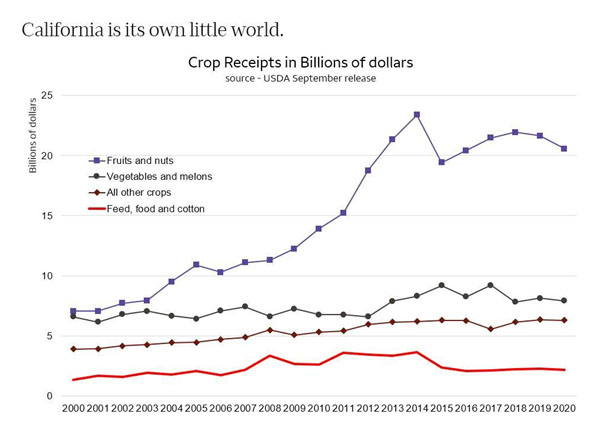

In the early 2000s, California generated $7 billion to $8 billion of revenue in fruit and nut crops. By 2014, that number had peaked at $23 billion. Since then, the industry has pulled back to $20 billion. The plateau has pressured operators that aren't efficient and have failed to modernize.

Vegetables, fruits and melons are among the other high-value, high-quality crops coming out of California. The state is just a mecca of incredible productivity.

While California has carved an impressive niche in some crops, the opportunities aren’t as clear in other products. For instance, California farmers can grow corn and grow it well, but can they compete with Iowa and Nebraska? Should they even bother?

The calculus is similar for wheat and barley. California farmers choose not to compete with producers in southern Canada and Montana. Cotton has been a staple in California for many decades. But with water costs on the rise, California farmers have been selective about the crops they grow. Farmers have focused on Pima cotton because it fetches a premium. On the other hand, selling basic cotton simply isn’t a good use of California farmers’ effort, time and water.

California is home to more than 80% of the global production in almonds. The state also produces a large share of the world’s pistachios. Being the premiere producer of those quality nuts gave California farmers a growth opportunity that was second to none. California’s shift into nut production coincided with the explosive growth of the Chinese market. California took advantage of that market in a very big way.

For a while, the joke was that the answer to every question about agricultural demand was China. The Chinese economy modernized and that export market saw a run-up in economic purchasing power, so Chinese consumers became very big buyers of many crops from the U.S. in general and California in particular.

Alas, a good thing doesn’t last forever – and that was the case with California’s farm boom. From the mid-2000s to about 2014, California growers’ cash receipts outpaced their cost structure by a remarkable amount. That meant there was a lot of new money that fell to the bottom line.

However, the Golden State is experiencing more profit pressure over the past few years. California is working its way through a lot more pressure than the Midwest right now. California farmers enjoyed an incredible run-up in profitability.

Of course, everybody is drives by looking in the rearview mirror. Investors flooded into almond production in 2015 and 2016. By the time investors figured out that the good times would pass by, planters had flooded the market with almond plantings.

Now that things have slowed, the question is, are we at a poor point of profitability, or was the recent history just too good? It’s possible that the period of 2012 through 2014 simple set expectations too high, and now the industry is returning to normal. But California agriculture has always been about owning the right land, with the crucial variable of having access to water. California farmers rely almost entirely on irrigation – there just isn’t enough rainfall to sustain the industry.

California’s agriculture industry has experienced a regression to the mean in recent years. Now that profits have returned to normal, some formerly profitable operations are actually losing money. So why don't they go out of business immediately? A lot of these companies are backed by deep resources. They've been around a long time. They don't have very much debt, so they could continue to operate for a long period of time, even if they experience very poor returns on assets. In any industry, capital needs to find good managers and good managers want to be paid for that management.

The use of leverage in agriculture

In many other real estate asset classes, leverage is a sure way to boost returns. In agriculture, though, the use of debt can be trickier. To underscore the challenges, let’s contrast agriculture with a wholesale industry, where an operator typically might turn assets 12 to 15 times a year. In general, more sales per dollar of assets is a good thing. The quicker turns give an operator more opportunities to make money.

But turnover isn’t so simple in agriculture.

Growers of fruit and nuts, for example, typically harvest just one crop a year, and it can take several years to establish an orchard just to harvest the first strong crop. As a result, the industry sees much lower returns. Agriculture is an asset-heavy, slow-turn model. One of the levers investors pull is leverage. Of course, borrowing money is a two-edged sword -- anything can be poisonous at the wrong dosage.

Wells Fargo is a very careful, considered lender, and that ethos applies to the bank’s agricultural lending. Borrowers need to understand that not everything is going to go their way. Heavily leveraged operators enjoy a lot of money falling to the bottom line when things go well. When conditions turn for the worse, indebted operators can run into trouble quickly.

The best operators use leverage responsibly. In a time of competitive pressures, a farmer might respond by leveraging up the risk. For instance, say the operator has $100 million of equity and needs to build a new facility for $200 million. Borrowing that much involves a significant ramping up of leverage. However, the best operators will be very intentional about whittling that leverage ratio back down. A good operator works very diligently to pull the leverage ratio below one as fast as humanly possible.

A banking regulation quirk that offers investors opportunity

One quirk of banking regulations that provides a fascinating opportunity for investors is that banks can only use the sales comparison approach when valuing a farm. It does not matter how many income producing trees or other crops there are on a farm, federal regulations restrict banks to looking only at comparable sales.

This reinforces the archaic way that land has been valued by farmers for generations and continues to be valued which is by the acre. It does not matter what the income is that a farm generates, farmers and their bankers alike look only to comparable sales per acre.

As incomprehensible as this may be to any savvy real estate investor accustomed to underwriting real property based on the net operating income using cap rates and ability to repay a loan based on debt service coverage ratios, it speaks to the extraordinary opportunity that Bravante Farm Capital is looking to exploit.

In the California oasis we are targeting with strong water fundamentals, farmland has been held for generations and when traded, traded on a per acre basis. Not only have farmers always thought of farmland valuations this way, but regulations have reinforced this methodology.

This is in stark contrast to institutional and ivory tower private equity shops entering the market. Removed (literally) as they are from the land itself, their underwriting requirements demand that they value the land based on its potential to yield ongoing income streams.

As more of these investors enter the field (if you will excuse the pun), so they will drive up values because they see not price per acre, but cash yield per invested dollar. Even if initially banks are unable to lend to increasingly outsized purchase prices because comparable sales do not justify the prices being paid, as more deeper pocketed investors enter the market, so those comparable sales will increase and banks will begin to lend more as their appraisals justify the increased price per acre.

And so an upward spiral of price inflation will hit farmland like never before in history.

What is particularly fascinating is that this likely will not impact food costs because all that is happening is that yields on capital being used to purchase farmland is being redefined. It is a rationalization of the farmland business, not an increase in costs in any way.

As farmland becomes increasingly financed based on expectations of returns on investment and not per acre, so prices for land will go up without placing upward pressure on the price of the produce being grown and sold. This will continue until the true value of the land reaches equilibrium with the yield expectations of institutional investors and their inherent cost of capital.

Here at Bravante Farm Capital, our strategy is to identify value add farms that are priced on a per-acre basis and that offer outsized long term yield potential. We will reap the benefit not only of outsized yield per invested dollar because we are buying the land at such relative low prices, but also of capital appreciation as the price of the land we purchase increases as it shifts from a price per acre formula (sale comparison) to a yield on capital formula.

In farmland, regulations have served to keep values down by prohibiting the use of the income approach to valuing land, reinforcing an antiquated pricing mechanism. At Bravante Farm Capital, our strategy is to capitalize on this dislocation in valuations by buying at an undervalued per-acre basis, enjoying outsized returns on our investment, and watching and waiting as the private equity and institutional investors drive up values by underwriting based on yield.

Surging Inflation Hits Consumers Hard

The investment appeal of farmland boils down to this basic truth: Everybody eats. That obvious reality underpins the value of agricultural real estate. A pandemic might dampen demand for office space and hotel rooms, and e-commerce might take a bite out of retail demand. But humanity has yet to experience a market shock that causes people to eat less.

While demand for food isn’t going away, and the supply of farmland isn’t expanding, the recent spasm of supply-chain issues has created new drama. Consumers are being squeezed by a pandemic-era spike in inflation.

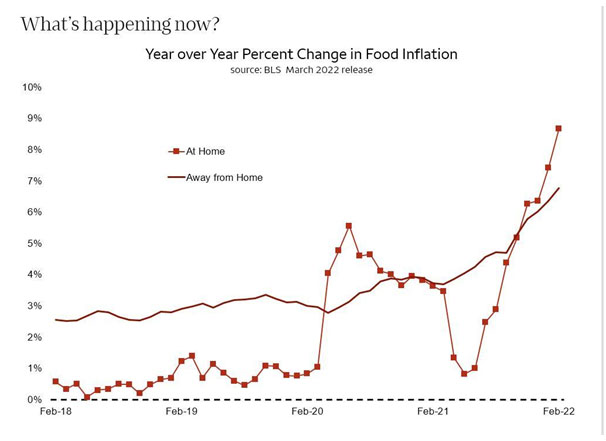

Today’s conditions pose difficulties for consumers of all income levels. In February, inflation in the category of “at-home food” (edibles bought in a store and consumed at home) soared 8.7% annually, compared to a 7.9% jump for the overall consumer price index. That’s the highest level of food inflation in 40 years. Prices are being pressured at the producer level by transportation costs, packaging cost, labor and other factors. And there’s no obvious end in sight.

Consumers simply aren’t accustomed to this type of inflation. Neither is anyone else in the agricultural supply chain. Prior to the past year, food inflation had averaged just 1.1% for the past 10 years. In other words, price increases were so subtle that no one really noticed them.

When prices are growing just 1% at retail, producers essentially can’t pass along price increases. So how does the producer grow profits? By innovating. In the decade leading up to the pandemic, producers learned to grow more fruits and vegetables per acre with less labor and less inputs. In that way, farmers squeezed out efficiencies and learned to competition, and profitability followed.

Nevertheless, farmland real estate provides investors with access to one of the most resilient inflation hedged options for their capital.

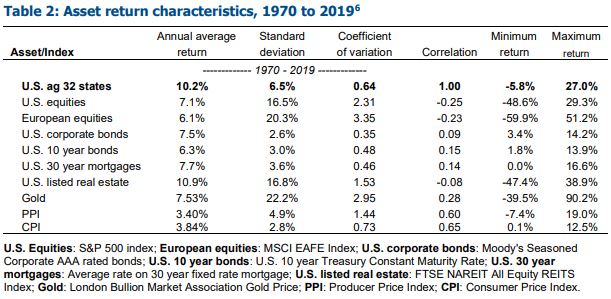

In the table below, you can see how different investment options have compared to returns on agriculture:

Source: TIAA Center for Farmland Research

https://farmland.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Relationship-between-inflation-and-farmland-returns.pdf

Last accessed Aug. 22, 2022.

The table shows that, overall, farmland yielded an average annual return of 10.2% for the 49 period through the end of 2019, and that the minimum return in any given year has been -5.8% which is just 12% of the most extreme drops in US Equities which experienced a drop of -48.6% during its worst year during the study period.

A synchronization of price pressures

Amid this post-pandemic shock to the system, the agricultural economy is experiencing a synchronization -- almost every input into food prices is rising. Intriguingly, there’s no shortage of raw ingredients.

But the food supply chain has been struggling for the last two years with the transformation process -- taking milk and turning it into cheese, taking grapes and turning it into grape juice or table grapes.

Packing, packaging, transportation, pallets, fuel costs, labor – costs throughout the freight process are rising across the board. It’s impossible to predict how long this inflationary cycle will last, but this dramatic price increase will certainly have a profound impact on the system as market players sort out who should be paying for what and what’s a reasonable profit margin.

It's a system shock that happens very seldom. But when it does, it can cause a major realignment in the value of assets in agriculture.

Money flows into the sector

The pandemic clearly changed consumer behaviors. Will this prove to be a structural change or a transitory change? Probably a little bit of both. Food service and food delivery is likely to adapt and evolve. It’s likely that restaurants will rely more on apps and more ordering from the table without a face-to-face interaction with a server. Especially among moderately priced eateries, diners probably will pick up their food at a counter type rather than waiting for a server to deliver it.

But here's a key point: A lot more money flowing into food services and the food and beverage store segment than ever before. It’s already a big sector, and it’s growing. This flood of capital will affect everyone in the supply chain -- fruit packers, fruit growers, vegetable growers, livestock operators.